Semper Fideles

Marine Corps Marathon, Washington, DC, October 24, 1999

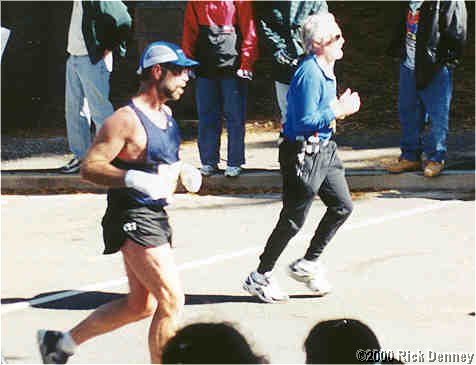

Me, at 26.1 miles.

At 5:30, I was rudely awakened by a loud fire-whistle sound. After determining that 1.) my name is Rick, 2.) this is my house, and 3.) it is not on fire, I realized that it was the alarm clock. Funny it should come as such a shock given that I had not remained asleep for more than two hours at any one time all Saturday night.

I got up and showered, and the phone rang. My peerless lady friend (he says, steadfastly avoiding the term "girl") had arisen early to wish me well. She was suffering from a cold, and I had consigned her to bed, only to come to the finish line if she was feeling better. That she allowed me to consign her to anything is testimony to how she felt.

As I was navigating the length of the Dulles Toll Road towards Arlington, it struck me that it was here. Marathon Day. Already. How could that be?

First thing: The Port-o-Potty. My watch read 7:30--an hour before the start. Sounds of a wedding ceremony wafted across the field surrounding the Iwo Jima statue that marks the Marine Corps Memorial. I looked around me: Thousands upon thousands of people walking around trying to keep themselves busy for another hour. The milling masses were surprisingly quiet--but I understood that. I thought about the road that led me here: The last person to be picked for the team throughout school, the Man Mostly Likely to Have a Heart Attack at Age 40 award that I received as a freshman in college, how I used to get out of breath walking down the hall to the Men's Room, and how I used to hide behind a fat body and avoid doing the things that I dared not admit I wanted to do. Now, I'm getting ready to run a marathon. Geekness cannot overcome the emotion of such a moment.

Second thing: The Port-o-Potty. I suppose my hydration plan for the previous four days had worked.

Standing in the baggage tent, I made a last assessment of temperature. I had the long-sleeve running shirt (a cheapie that could be discarded--thanks for the advice from many). I had a singlet, with number already attached. I had gloves, in addition to an old extra pair of socks to be used as throw-away mittens. I decided to go with the singlet and the socks. After standing around for a few minutes, I wasn't shivering, so I thought it would be about right. It was.

I could not find the signs marking the projected completion times at the start, so I lined up about two-thirds back. I saw them later--on balloons so high I hadn't looked high enough. A blur of activity: Marine Band of Quantico, the Deputy Commandant of the Marine Corps, a chaplain, a gunnery seargent who, on a warm morning, could probably have sung the national anthem pretty well. There was lots of cheering all around me, but I could not spend my energy that way.

The gun went off in typical Marine overstatement: a 105-mm Howitzer cannon. 18,000 runners started oozing towards the start gate like thick syrup. I was in no hurry. I crossed the line ten minutes after the gun, depending on the ChampionChip to record the proper time of my own beginning. We broke into a collective trot.

The first three miles or so averaged about 10 minutes, plus 20 or 25 seconds for the first water stop. Inexplicably, my bladder was full again (I had drunk only about 20 ounces that morning, and no caffeine), but the lines at the Port-o-Potties at Mile 4 were 15-deep. We had run from the Iwo Jima statue past the Pentagon, through Pentagon City, and back, right up to the door of that famous building. It takes a long time to circumnavigate that edifice. When we approached it, however, we got a glimpse of the leaders going the other way--already two miles ahead.

We passed by the start again, going north into Rosslyn, the downtown of Arlington County. My bladder was so full that I had previously contemplated following the dozens of runners, of both genders, that I had seen relieving themselves by the side of the road while there were bushes to hide behind. I wish now that I had--the concrete jungle now admitted no such opportunity. We crossed the Key Bridge into Georgetown, with the spires of George Washington University guiding the way.

Finally, just shy of Mile 8 another batch of Port-o-Potties appeared. I vibrated with frustration for four minutes waiting for merely two people in my line to do their business. I took 15 seconds. I came out of the chemical toilet angry at the delay, with a rush of adrenalin. My pace quickened therefore to 8:50 miles, which I maintained for three miles before adrenalin subsided and good sense prevailed. By that time, we were monopolizing Constitution Avenue, past the be-scaffolded Washington Monument, to Capitol Hill.

I had lined up too far back. I had been working my way through the crowd like an impatient commuter weaving through heavy freeway traffic. The Galloway Walkers were the worst: There would be a group of them, 20-strong, that would suddenly slow to a walk at the signal from their official pacer. We would pile into them like too much water in a funnel, roiling through as best we could. How did they get in front of me?

My watch at the halfway point read 2:11:33. My goal was to finish in 10-minute miles, on average, so I knew that I had to maintain my speed for the rest of the race. Things were starting to hurt, though, and doubts ate at the corners of my thought. We wound our way back down the mall to the Lincoln Memorial, and then south on Ohio Drive to the Jefferson. Ohio Drive was a two-way part of the course, and I was amazed that the crowd going the other way, something like five miles ahead, consisted of the same sort of people in my part of the stream. We passed the Waterfront and went out onto Hains Point.

Hains Point is like Heartbreak Hill in Boston. It's not a hill--quite the contrary--but it is undeveloped and orphaned by the road closures. That means no spectators. But the wind had easy access, and the sun was hiding behind clouds. It was cold. And then a feeling of malaise started to grow on me. Things started to hurt more. People around me started to cramp up. As we rounded the tip of Hains Point, we crossed Mile 18 and turned into the wind.

One problem of being my size: there's nobody out there big enough to hide behind. I was cold, and becoming unhappy. A tiny woman passed me--she could not have been more than five feet tall. But she was just about the only person who had passed me in the whole race, and I though I'd pace her for a while. For the next two miles, I realized that it didn't hurt any more at a 9:20 pace than it did at a 10:00 pace, so I kicked it up. She cramped up at Mile 20, though, and I was on my own.

There comes a time in each race when thoughts turn doubts about finishing to conviction that the race will be completed. I stopped again at a Port-o-Potty, and again wasted two minutes. This time it was a real waste, however, because even though the bladder felt full, nothing came out. Immediately thereafter, I passed the 22-mile mark. Suddenly, it occurred to me that I would finish this race, and further, that I had the mental will to suffer to do it. I kicked it up again. The realization came not with happiness, but with an inexplicable mixture of pride and humility that brought me to the brink of tears. I could now understand the primal displays of emotion during an Ironman.

I onced said that an Ironman seems to reveal who you really are. Early the race, there was anger. But later, when all that had faded, there was something else. Maybe in 9 months I'll be able to explain it.

I was no longer easing past people. Now, I was flying by them. Most folks had slowed to 11 or 12-minute miles. I sped up and ran 9-minute miles. Miles 22-25 went by in 27:30, including a walked water stop.

The 14th Street Bridge is a milestone in the Marine Corps Marathon. Crossing it means that you will be allowed to finish under your own steam no matter what. We passed the Pentagon for a third time, and again ran north on the Jeff Davis Highway to the Marine Corps Memorial. During that last mile, I was thinking, ignore pain, ignore pain. I had stepped up the pace for the last four or five miles, all the while knowing that the real test was inside my head. I didn't slow down until I topped the hill, facing that great icon of determination and grit, the statue of marines planting a flag in a place well defended by bitter enemies. Their's was the vastly greater challenge, and their's was the monumental triumph. My finish was a little thing.

I didn't appreciate the symbolism of the moment, though--that came later. I just wanted to sit down. The "volunteers," who are all wearing fatigues, shuffle you through the chute, hang the medal around your neck, salute smartly (which I was ready to return just as smartly--but when the time came I just didn't have it), remove your chip, and direct you to the freebie tent where you can get water, bananas, bagels, oranges, and other nauseating concoctions, but not one single place to sit down. After the tent, they spit you out into an area where someone was hawking "step forward and get your picture taken for a free proof in a week."

I passed by to the right, and found an area of relative peace surrounded by 30 or 40 thousand loved ones looking desperately in an impossible crowd for their favorite weary marathoner. I sat down on my space blanket and drank the water. Another fellow was sitting next to me, and another fellow on the other side. We spoke no words to each other. We didn't even meet each other's gaze. One of the fellows looked like the war-weary soldiers in Saving Private Ryan. I figure the actors in that movie ran a marathon, and they then filmed them that afternoon.

The crowd was frightening for anyone who prefers air to breathe. I had no energy to force my way through, and honestly, that crowd will keep me from doing another big race like this. Run a marathon--fine. Spend 15 minutes being touched on all sides by strangers--I don't think so. Some people take energy from crowds, and I'm always reading reports here about how the incessant woo-hooing charges them up. It doesn't me. Instead, I remember being afraid of the crowd--like they were going to swallow me up. The best parts of the race were the lonely stretches out to Hains Point and the long Potomac crossing on the 14th Street Bridge with just the steady rhythm of falling feet to keep me going.

I finally worked my way to the baggage tent, retrieved it, and continued up the hill to the A-F Meeting Area. At this point I had only one remaining objective.

She has red hair and she's tall, and I spotted her instantly, like in the old movies where everything else fades to black except for the central spotlight. She was searching, intently looking the other way. For me. I touched her shoulder.

Rick "4:19 and change" Denney