Hartblei 45mm PCS

Is Perspective Correction Just for Architecture?

In the world of Kiev cameras and lenses, few lenses are marketed as being new and of professional build quality. But the Hartblei company, which seems to be based in the Ukraine but not officially connected with the Arsenal factory, makes just those claims. One of their offerings that attracts a lot of attention to professional photographers is the 45mm PCS lens. The lens has been built in three versions. The earliest allowed a horizontal shift in any direction of up to 12 mm. The next version provided a tilting capability, and the latest version, called the Super Rotator, allows a more flexible tilting and shifting barrel.

Mine is the simple shifting lens. In fact, this lens uses the same optical elements as the Mir 26b 45mm lens made by Arsenal. Clearly, Hartblei gets the optics from Arsenal, multi-coats the elements, and mounts them properly in a barrel of their own manufacture. The finished appearance is what I would call Spartan rather than luxurious.

The Hartblei 45mm PCS lens, as pictured by Kiev Camera on their advertisement. This lens is #3, mine is #55.

Given that it is a lens designed for non-shifted coverage of the 6x6 image circle, I was curious about the performance in the extremes of the illuminated circle outside the intended image area. The performance of the glass itself is typical of the best of the Mir 45 mm lenses, except that it displays much less flare. The improved flare performance can be attributed to the multi-coating applied by Hartblei.

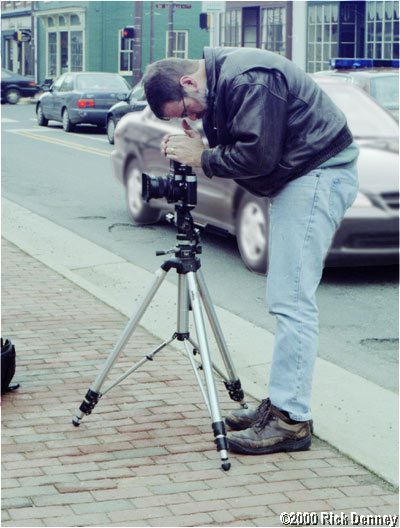

Me, using the Hartblei lens. Note that it is shifted upward.

The Hartblei comes with a round shade, but I prefer the square shade that is made for a 45mm lens for the Pentax 6x7 of the same size. In the photo above, I have intentionally blurred and lightened the background car so that the configuration of the lens is easier to see.

So, why use a shift lens? Is it just for architecture?

The whole point of a shift lens is to avoid the convergence of parallel lines as they recede from the camera. This is the effect of perspective, where distant objects appear smaller than nearby objects. When you tilt the camera back to get the whole subject into a frame, the vertical lines of the subject are no longer parallel to the film. Where they are farther, they recede. The solution is to keep the film vertical, so that the vertical lines in the subject are parallel to it. But sometimes this cuts off an important part of the picture. That's where the shift comes in--you just move the lens sideways or up and down until you can see the whole subject.

Let's look at this effect, and at some specific performance issues with this lens:

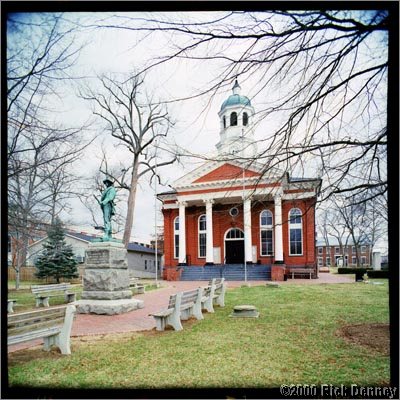

The Loudoun County Courthouse, Leesburg, VA. 1/60 at f/8, Agfa Ultra 50, 12mm upward shift.

The basic image above shows the extreme capabilities of this lens. Firstly, notice the darkening of the upper corners. This shows the limits of coverage for the lens. Notice also that the images in the corners get quite fuzzy. The field has become extremely curved here, and the image isn't focused in these corners. The fuzzy edge at the bottom is also interesting. Is this the shadow of something in the mirror box? I don't think it is vignetting from the shade--the coverage angle is sharper at the top edge. Finally, these lenses have a reputation for unacceptable barrel distortion. Do you see it? Neither do I.

Let's look as some of these issues in detail, starting with the corners.

Detail, from above.

This scan was taken from an Acer 1240ut, at 1200 pixels/inch. The overall image would be about 25" square, assuming your monitor resolves about 100 pixels/inch. The scanner is not perfect, but the lower left corner shows you what it can do. As you can see, the lens shows extreme chromatic aberration (the blue fringing). Also, the field is curved and the image goes out of focus. The 12 mm shift position is marked in red on this lens, to warn you that you're pushing the envelope.

In the paying part of the image, the performance is reasonably good, as shown here (the little bit of red fringing is caused by the scanner):

Detail, from column capital.

As stated in the Lens Testing article, the performance of the lens is reasonably good and displays similar resolution to the best of the Mir lenses (and far better than some of the reported poor examples of the latter).

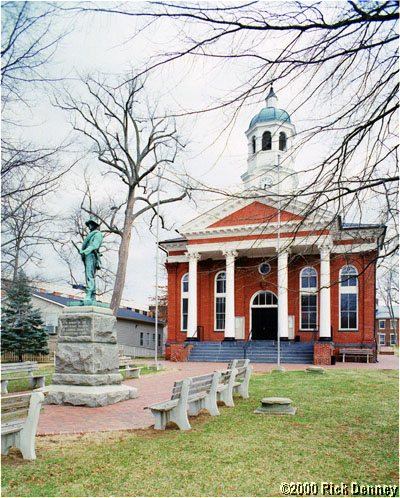

With a little judicious cropping, the offending fuzzy corners can be removed, resulting in the finished image, below:

Finished image, cropped to 8x10 proportions.

There is still a bit of fuzziness in the corners, but I refused to reduce the wide coverage of this lens so that I would see what I would get in the worst case, and for most subjects this would be acceptable. It is also true that I could have composed this image with only 10mm of shift and avoided the problem altogether, but I wanted to test the lens at the extremes.

If the lens has any barrel distortion, it is not obvious in this picture.

The shot below is designed to make any barrel distortion glow in the dark. This image is cropped only slightly to correct for a slightly askew composition.

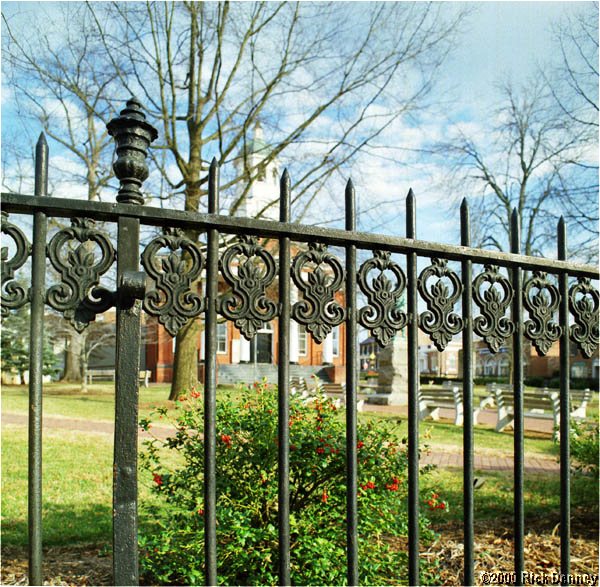

Iron Fence, Loudoun County Courthouse. 1/250 at f/5.6, Agfa Ultra 50.

You can see the barrel distortion here, but again it is not painful. Notice that I did not attempt to correct all the perspective distortion in this image. I wanted the fence to look as though I was looking up to it. Quixotically, the out-of-focus background goes sharp in the upper corners near the edge of the field (most of this was cropped out), which demonstrates that the fuzzy corners are a field curvature problem.

Some have said that this lens is useless because of barrel distortion--the one unforgivable sin in an "architecture" lens. But I don't think of this lens as an "architecture" lens, unless you include God's architecture. The shot below illustrates the point:

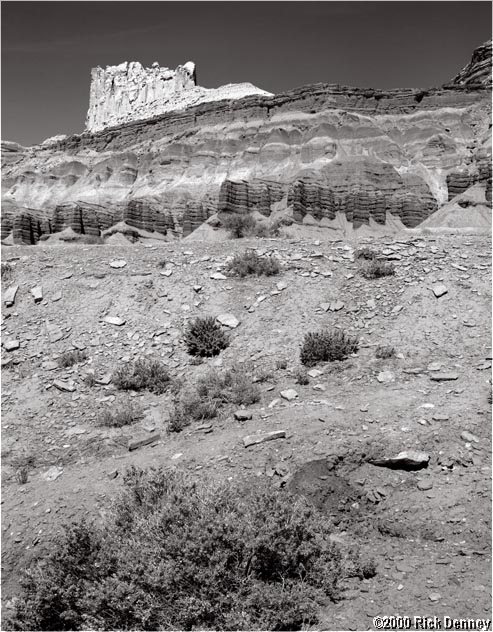

Castle Rock, Capitol Reef National Park, 1992. 90mm Schneider Super Angulon on 4x5 film, 1/60 at f/32, Ilford FP4.

I made this image a few years ago with a view camera, using the shifting front to maintain parallel between the film and the vertical formations. This image would lack drama without perspective correction.

A perspective-correcting lens for a roll-film camera is a compromise. We'd rather use a view camera. But often that is just not possible, and a wide-angle lens with the ability to shift is just the ticket. For the same price, or less, as a used non-shifting wide-angle for another medium-format camera, the Hartblei can be bought new, and provides a reasonable amount of shift.